It’s time for Croatia to embrace the European Green Deal

Average temperatures are rising more and more in the Zagreb region, while snow cover is decreasing year after year. However, Jagoda Munić, Director of Friends of the Earth Europe says that “Croatia is a very passive observer of developments around the European Green Deal.”

The average temperature in Zagreb in 2019 was higher than in any previous year, and at the same time the capital of Croatia recorded the lowest number of days with snow cover. This can be seen in Statistical Information 2020 , recently published online by the Central Bureau of Statistics of Croatia.

Data was collected from three measuring points:

- In Maksimir, a district on the east side of the city, which benefits from the freshness provided by a dense oak forest and several lakes, the average air temperature was 11.2°C fifteen years ago. By 2019, it had risen to exactly 13°C.

- On Grič, a hill rising above the very centre of the city, the temperature rose from 12 to 14.2°C in the last fifteen years.

- On Puntijarka, which is located 957 meters above sea level, the air temperature has risen from 6.6 to 8.7°C in the last fifteen years.

>>> READ ALSO – European Parliament pushes for greener targets in new climate law

We talked about these results with Jagoda Munić, current director of the international organisation Friends of the Earth Europe , and formerly the long-time president of the reputable Zagreb environmental association Zelena akcija (Green Action).

“The data does not surprise me at all and only confirms the forecasts of scientists, who worked on the development of scenarios for the impact of climate change on the climate. So, global warming predictions are coming true, and even faster than projections,” said Munić.

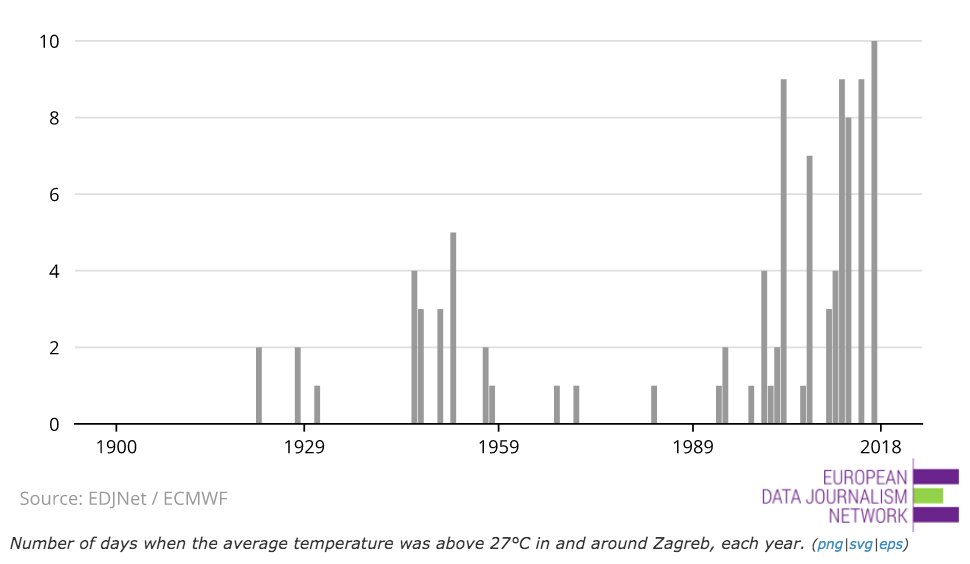

When the data on air temperature from the last fifteen years is compared with the long-term trend, the assessment of Friends of the Earth Europe’s director is even more strongly confirmed. As EDJNet reported, the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts finds that Zagreb and its surroundings have almost regularly had at least 8-9 days with an average temperature above 27°C in the last ten years; in the first half of the 20th century there were almost no such days.

Rising air temperatures necessarily lead to the gradual disappearance of snow. In the winter of 2019-20, snow fell only once in Zagreb. Last winter, the Croatian capital was not covered with snow for a single day, so the Croatian Bureau of Statistics (CBS/DZS) data for 2019 actually refers only to the first months of the year. On Grič, the number of snow-covered days has dropped from 16 to only 6 since 2004. In Maksimir, it has also dropped, from 17 to 8. In the future, children from Zagreb will only be able to enjoy scenes of snow-covered Zagreb streets and rooftops by looking at old photos.

Puntijarka, located 957 meters above sea level, near the scene of slalom races organised as part of the World Ski Cup, has recorded a decline in the number of days with snow cover from 95 in 2004 to 71 last year. We asked Jagoda Munić to comment on whether the perspective of the ski complex on Medvednica, whose most glamorous event is the hosting of an international ski competition, is now uncertain with such a climate trend. Is there an ecological justification for holding the World Cup on Sljeme, with mass artificial snowing of trails, and the construction of traffic, sports and accommodation infrastructure?

“Medvednica is very important for the local climate, air quality and flood protection in Zagreb. In the last ten years, forest devastation by felling and uncontrolled traffic of off-road vehicles have significantly worsened the situation. The top part of Medvednica has the greatest pressure due to ski resorts. Green Action warned in the early 2000s that it was better not to build ski resorts on terrains below 1500 meters above sea level. I am afraid that skiing on Sljeme has no future, because there will be no snow, and the question is the cost-effectiveness of making artificial snow and its impact on nature due to the use of chemicals,” says Munić.

>>> READ ALSO – Unhealthy environment makes unhealthy Europeans

The need to implement the European Green Deal

Immediately after the parliamentary elections, which were held in early July 2020, eighty associations and other organisations concerned with protecting nature in one way or another, sent the Parliament and the new government a list of requests entitled “Together for Croatian Green Recovery and Development”. The signatories declared that, “If not addressed urgently and systematically at the level of each country, the climate crisis will have even more drastic consequences for the economy and humanity in the long run than those caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Green recovery is therefore the only possible path, which, while contributing to tackling the climate crisis, enables job creation, reduces healthcare costs and guarantees a fast and efficient step into a new, low-carbon future with less inequality and a resilient and competitive economy”.

Their demands cover various sectors, from the harmonisation of all national climate and energy policies with the European Green Deal, the suspension of investments in the fossil fuel industry, the reconstruction of buildings in Zagreb after the earthquake in compliance with the highest energy standards, to a strong transition to low-carbon development and job creation.

We asked Jagoda Munić how much Croatia is actually deviating from the realisation of the European Green Deal and whether there is scope for progress. “I am afraid that Croatia is a very passive observer of developments around the European Green Deal,” she stated. “Even during the Croatian presidency of the European Council, I did not notice any initiative. It is certainly important that, especially in light of the economic recovery following the coronavirus pandemic, economic development is geared towards a green and equitable transition to a low-carbon economy. In this regard, the demands of civil society organisations should be met.”

According to Munić, the first step in approaching the European Green Deal must be to abandon investments and permits for fossil fuel exploration projects, and to focus on renewable energy sources, energy-efficient renovation of buildings and transport models that are less harmful to the environment, e.g. electric and accessible public city and intercity transport. In this transition, Mujnić believes, it is important to take social justice into account, because the cost of the ecological transition must not be paid by the poorest. If we want to make the transition in such a way that poverty and economic inequalities are reduced, and well-being is broadly increased, then it is important that this criterion is also taken into account. In practice, this means that the measures implemented must reduce so-called energy poverty.

“A good example is France, where rising fuel prices due to higher taxation have led to yellow vest protests. Automatic increases in fuel prices without ensuring quality and affordable public transport affect the poorest segments of the population. Another example might be the co-financing of electric vehicles by the Environmental Protection and Energy Efficiency Fund. Now, I will not go into details about the problematic ‘fastest finger’ allocation of funds, i.e. whoever clicks at midnight when the tender opens, gets the funds, but I will touch upon the very essence of such funding.”

“Namely, investing in co-financing a small number of private cars (and encouraging foreign industry) does not make a significant contribution to reducing pollution, if city traffic is poor and most citizens cannot buy a new electric vehicle even with an incentive, but drive 20-year-old diesel cars. The ratio of what is invested and what is gained in this case is by no means favourable.”

>>> READ ALSO – World lost 100 million hectares of forest in two decades: UN

Jagoda Munić, Friends of the Earth: Let’s look at Costa Rica

It is widely believed that the responsibility for global warming lies solely with the most industrialised countries, and that solutions can only be reached globally. Meanwhile, semi-peripheral local communities are left to monitor developments and hope for the best. What can be done in this regard, for example, at the level of the city of Zagreb?

This is a common view in Croatia, which has taken the position of a small country on the periphery. Croatia can do a lot. Actually, the fact that we are small and that we still have a relatively high-quality environment and nature (which we are rushing to destroy) may be our advantage. One good example of a country of similar size and population, whose historical context is not much better, and has done much, is Costa Rica. The difference between us and them is vision. Croatia does not have a development vision. Independence and EU membership are the closest we have to a vision, but on top of that, we don’t even know what we want to be as a country other than a small country on the European periphery, dependent on tourism and EU funds.

On the other hand, it is precisely a small country with such predispositions that can be rapidly directed towards sustainable development. In the next five years, we must launch a green and equitable ecological transition while increasing the resilience of ecosystems and society to the effects of climate change.

More specifically, at the level of Zagreb, post-earthquake reconstruction should be carried out in a way that increases the energy efficiency of buildings, facilitates the installation of solar collectors on roofs and construction of green roofs, improves efficiency and accessibility of more sustainable public transport, and reduces the use of passenger cars in urban transport. As for resilience against climate change, we need to modernise the stormwater drainage system, increase the number of green corridors, parks and trees in the city in general, create a natural system that would reduce the impact of greater precipitation fluctuations (drought-flood) and temperature fluctuations (sudden rise and fall in temperature). Also, the devastation of Medvednica must stop immediately.

>>> READ ALSO – EU executive proposes emissions cuts, climate bonds for green Europe

The European Green Deal

The European Green Deal was drafted by the European Commission in late 2019, as an attempt to establish, as stated, a new growth strategy for the EU that aims to transform the EU into a fair and prosperous society, improving the quality of life of current and future generations, with a modern, resource-efficient and competitive economy where there are no net emissions of greenhouse gases in 2050 and where economic growth is decoupled from resource use. As the introduction to the text states, it seeks to “protect, conserve and enhance the EU’s natural capital, and protect the health and well-being of citizens from environment-related risks and impacts. At the same time, this transition must be just and inclusive.”

Source: EDJNet / H-Alter